〈.pdf〉

〈audio〉

Muscle Memory: How Archery Helped Me Learn to Read for Fun Again

Prologue

When I was a kid, I didn’t particularly like exercise or sports, in large part because (1) my experience of exercise was mostly in school gym class, (2) I wasn’t very coordinated, and (3) it’s not very fun to do things in front of an audience of your peers when you’re bad at it. All of this, of course, is further compounded when you have a set standard for performance fixed in your head and you’re worried that aren’t meeting it.

Is this the face that won a thousand dodgeball games and excelled at track and field? No, it is not. (Also picture here: Most Michigan snowman to have ever been constructed).

You are probably thinking, “But wait! Isn’t this a literacy narrative?”

Stay with me.

Act I

Two of my most vivid early memories involve literacy. The first involves reading a children’s book aloud, likely If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, from cover-to-cover on my own for the first time (there is a good chance that I had in fact memorized the words on the pages and wasn’t actually reading, but at the time, it felt like a serious victory and I was proud of it). The second memory involves being asked by my teacher in pre-K to spell my last name—I very vividly remember furrowing my brow, looking up at the fluorescent lights on the ceiling, and getting it right, very slowly: “S-L-A…Y-T-O-N.”

Classic.

These two memories are pretty good summations of both my childhood and how I came to be where I am now—a doctor of medieval English literature, working both as a freshmen composition teacher and as a consultant in a communication center. I probably have to thank/blame for this trajectory all of the people in my early years who themselves were invested in literacy.

My mother, Linda Slayton, in her classroom.

My mother chief among them, who after staying at home with me and my siblings during our younger years went back to school and became a certified elementary school remedial reading teacher; but also many teachers, especially in elementary school and middle school, who gave me an option to do extra reading (yes, I did it) or do creative writing projects instead of papers (yes, I did them). I am probably one of very few elementary school kids who very frequently chose to skip recess and instead just stayed inside and read.

A kid who definitely did not know how to get anywhere.

When I did play outside for recess, it usually involved my like-minded friends and I recreating the latest Babysitter’s Club book we had read on the playground. I think I must in fact be the only kid who ever got chastised for reading too much—literally anywhere my family went (driving to the movies, driving to a restaurant, driving to the grocery store, driving to school), I took a book with me and read, and my dad once said—YOU NEED TO STOP READING ONCE IN A WHILE AND PAY ATTENTION, OR YOU’LL NEVER KNOW HOW TO GET ANYWHERE. I immediately protested that I must be the only kid who ever got told to read less. He wasn’t wrong, though. Thank God that they developed smart phones and GPS while I was in college.

Act II

Confession. In the past five years or so, I’ve only read a few books for fun: the Binti trilogy by Nnedi Okorafor, and the first two installments of the Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin.

At some point during graduate school, reading became my job. And because it was my job, and because I’ve struggled most of my life with imposter syndrome, reading for fun became not fun because (1) my experience of reading was mostly now for “work,” even though I genuinely enjoyed that work, (2) I didn’t think I was very good at academic reading, and (3) it’s not very fun to do things that you are now worried that you’re bad at, or least, not as your hobby. The physical act of reading—the actual pose, sitting in a chair and holding a book with my spine hunched, chin down, eyes fatigued—became a muscle memory that I began to associate with work, not with relaxation.

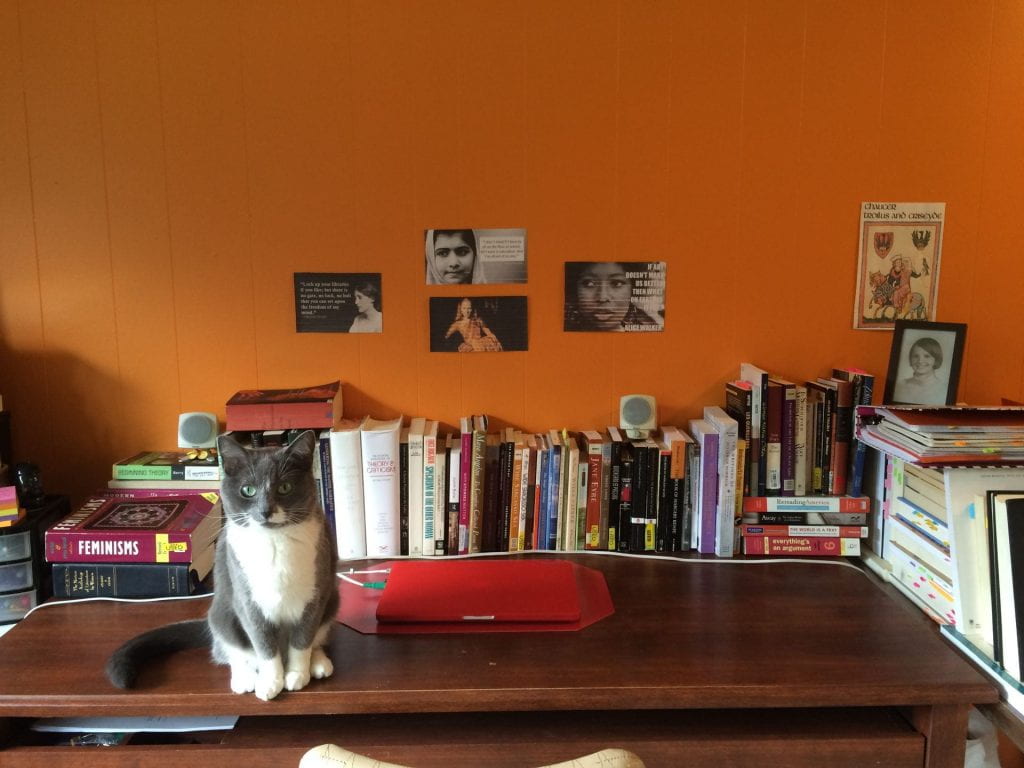

My workspace during my PhD comprehensive exams.

Eventually, after I finished my PhD comprehensive exams in 2016, I realized I needed to turn to something for fun, even if it wasn’t reading, my long-time but now abandoned hobby. In fact, I realized that maybe I needed to do something the opposite of reading—the opposite of sitting in a chair and holding a book, spine hunched, chin down—and I turned to archery.

I had tried archery a few times. I lived in Yamanashi-ken (山梨県), Japan for three years after college, working as an instructor of English as a Foreign Language with the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program. About a 30-minute drive up the mountain from my little inaka village of Misaka-cho (御坂町) was an outdoor archery range, Kagami Field Archery Club.

Kagami Archery Club Range

You could book big group visits, where everyone got beginner’s rental equipment, a thirty-minute crash course in “How to Not Accidentally Kill Yourself or Other People With a Bow,” a full BBQ (this deserves another essay) and then several hours to spend either at target practice or on the 3D course that meandered through woods filled with such delights as the infamous MURDER HORNETS that you may recall as the next 2020 moment from March.

Hungry archers.

My burnt-out, in desperate need of a non-reading hobby, post-comps self remembered enjoying archery and even being vaguely decent at it (for a noob). So, I did a quick Google search for archery clubs nearby (Knoxville, TN at the time) and had the luck to not only find a club, The Olympic Arrow, but one run by an archer with Olympic-level training. I signed up immediately.

Act 3

Coach Tworek’s shooting range.

My archery obsession developed instantaneously. It helped that it was early fall and so archery lessons were still in what archers call “outdoor season,” which meant that instead of sitting hunched over at my desk inside, I got to go outside and shoot in the sun, with fresh air and birds and trees. My coach’s backyard range felt like an Eden of sorts compared to my grad school workspace; yard enclosed by tall, stately trees, its edges adorned with lush herb gardens and flower beds. I started off practicing about once a week—all I could fit in, I rationalized at the time, what with grad school and teaching. By two months in, I was hooked enough to buy my own bow and practice two times a week. A few weeks after that, with the advantages of practicing more often becoming more and more noticeable on my target and scorecards, I began practicing three times a week, more if I could. I found myself discovering muscle groups that I barely had known existed before archery—scapulae! Lats! Triceps! Deltoids!

Archery, however, requires patience. While the length of a single shot cycle is fairly quick, perhaps fifteen to twenty seconds, archery itself is not a quick sport. You don’t start archery and magically become phenomenal at it in the span of a few days or even weeks (or even months). This is largely because the speed of the shot cycle belies its intricacy: nock your arrow; push your thumb pad gently into your riser as you raise your bow, the index finger of your draw-hand hooking gently above the nock, the middle and ring finger gently below; draw back using your scapula, loading the weight of the draw onto your back; anchor your draw hand firmly against your jaw, string making contact on the same precise space on the tip of your nose and the corner of your mouth each time; aim at your target, letting the blurred sight of your bow settle onto the in-focus X-ring; feel the tension in your back gently increase; release, draw-hand shooting back behind your earlobe, tracing the line of your jaw, bow hand pushing forward, scapula tightening and chest opening as your arrow flies toward the target.

Olympian Brady Ellison demonstrates his shot cycle (seen here anchoring).

Learning this process is humbling. When you first start, you will stink. This is in part because even if you’re already a pretty fit person, the muscle groups that you use for archery aren’t commonly used in your day-to-day routine. And even if you consider yourself a gym rat and you do target those scapulae and lats and triceps and deltoids, the precise movements that you use them for in archery require hundreds of hours of training to develop the muscle memory you need for success. Archery is a sport of consistency, of reducing variables, and it takes time to build the skills you need to achieve that consistency and see results.

What this means is that a few weeks into your archery training, you may start to hate it, or at least, you may start to get frustrated. You’ll keep missing the target. Even if you hit the target, you’ll keep having arrows land everywhere on it instead of a consistent grouping. You’ll smack yourself in the arm with a string and it will hurt like a *@#^ and you’ll need an ice pack and you’ll have a goose egg on your arm for a week and a bruise for a month. You’ll know that you are doing something wrong, but you won’t know what, so you won’t know how to fix it. You may feel like quitting, because (1) you may feel like you’re back in gym class, and this was supposed to be FUN, a new hobby, not WORK, damnit, (2) you might not feel like you’re very coordinated, and (3) it’s not very fun to do things in front of others when you’re bad at it.

Holding my first bow of my own in 2016

But here is where the biggest benefit of archery comes into play, if you stick with it. Archery doesn’t only train your body—it trains your brain. If you can get past those initial urges to quit in frustration a few weeks in, irritated that something that was supposed to be your hobby is now so exasperating, you will start to develop a new kind of patience. You will learn humility. You will find that your skin gets thicker. You will start to trust yourself more. You will develop an ability to tune out the world around you, thinking only about the sensation of your riser pressing against your thumb pad, the feeling of your scapulae coming smoothly together at your release, your shoulders opening up and the fingers of your draw hand brushing against your neck. Eventually, you will realize that it doesn’t matter if the other people in your class have a livestream of your failure, because you aren’t doing this for other people; you’re doing it for yourself.

Shooting 70 meters at the Tennessee State Championship in 2019.

More importantly, you’re not really failing; you’re still learning. This mental epiphany will lead to physical results, too, because in archery, you are what you think you are. If you tell yourself you suck, you will suck. Your body literally channels what your brain is thinking, in your posture, in small, otherwise infinitesimal movements, in the down-trodden, hunchback, sloped-shoulders posture of defeat. But if you tell yourself that you’re improving? If you tell yourself that it’s a work in progress, and that you can’t change past shots but you can work on future ones? Then you will start to unleash yourself. And you’ll get your hobby back.

Finale

I did promise that this really was a literacy narrative.

By mid-April or so of This Our Year of the Pandemic 2020, I found myself in a position much like I was in after my comprehensive exams—spending far, far too much time at my desk, hunched over, typing and reading all day, staring at a screen. But this time, archery wasn’t an option for me—understandably, the ranges shut down because of safety concerns. TV was scarcely an option, either, because after staring at my double computer monitors for 10+ hours a day for work, I couldn’t bring myself to look at another screen. And so, for the first time after a long, long hiatus, I looked at my fun-reading bookshelf.

If you take a hiatus from archery, it will be hard to pick back up, at first. Your muscles will hurt. They will not move the way they are supposed to. You will know, intellectually, what you are supposed to do but you won’t have the physical strength or finesse to do it. Your body will protest. I’m facing this now as the ranges and clubs start to open back up. But if you stick with it, it will come back; if you stick with it, you’ll find that it gets easier and easier again; that the muscle memory comes back; that it doesn’t feel like just something you should do, but something you want to do, again.

The number-one surprise of archery that has remained with me these past four and a half years is that its mental lessons translate to all facets of life. The thick skin that archery lent me helped me tackle readers’ reviews during the revise-and-resubmit phases of publishing academic work, for example; the patience and perseverance that archery taught me helped me survive the behemoth undertaking that is writing and defending a dissertation. But the most important thing? Archery taught me that to truly enjoy something, I have to do it for the right reasons—I have to do it for me, not for someone else. And more so than that, archery reminded me that self-care needs to be a habit to become effective, and habits require work—conscious dedication, not “fitting it in if you have time” (you never will if you leave it to chance).

And so, when I turned to my fun-reading bookshelf again, I had the tools at my disposal—from archery, no less, shocking for a kid who had always thought they hated sports—to relearn how to read, not for work, not for other people, but for me. This is not to say that it was easy. My pandemic-brain could barely pay attention for more than five or ten minutes at a time, at first. What is wrong with me??, I thought. How can you be an English teacher and be so bad at reading for fun?? But I remembered how archery felt, in the beginning. I remembered the reward that followed as I stuck with it, once I finally got over doing with other people in mind and instead just did it for myself. So, I set a goal of at least 10 minutes of fun reading per day. And the first few days were difficult. But eventually, I found myself reaching for my book instead of doom-scrolling on my phone. I found myself turning my TV off after just one episode so I could find out what happened next in my book, The Fifth Season by N. K. Jemisin, to see if Essun could survive the rifting long enough to find her daughter. I found my mood improving immensely, even though I chose to read a trilogy about a science-fictional apocalypse (we can psychoanalyze that in another essay). I started to feel like that kid, again, who skipped recess just to read, who read just because it brought them joy, not because they were “supposed to” read. I finished the second book of the trilogy last night, and as I write these final lines, I find myself glancing over to my bookshelf, where I know the third and final book is waiting for me.

Note: The author of this narrative has asked to remain anonymous.